How to build real muscle using bodyweight methods: Part I

Finally the tide is starting to turn.

Young and old athletes (and wannabe athletes) are switching over to calisthenics in their droves. There is a growing consensus that if you want a coordinated, supple, mobile, functional body, the best way to get it is using your body’s own weight. Rubber bands, plastic gadgets, cables, machines and infomercial ab gimmicks are out. The floor and the horizontal bar are in. We’re going old school, baby!

But what a lot of athletes (and coaches) still don’t realize is that bodyweight is also an awesome tool for packing on slabs of dense muscle mass.

Yes, you can see a lot of incredibly powerful bodyweight athletes with fairly low levels of muscle mass performing ridiculously impressive feats like muscle-ups, the human flag, one-arm handstands and whatnot. That doesn’t mean that bodyweight training doesn’t increase muscle mass—it can (and much more effectively than current bodybuilding methods).

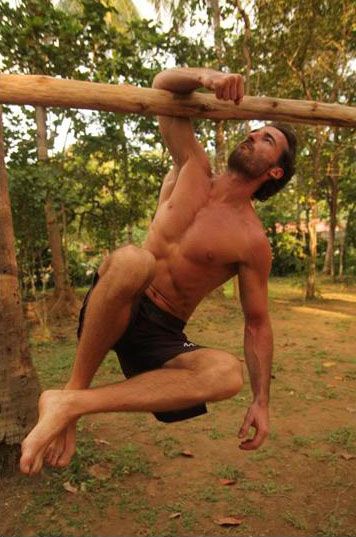

Lionel Ng is built more like a karate master than a bodybuilder. But he has trained himself to perform impressive feats of total-body strength—like the one-arm elbow lever and the human flag—using calisthenics. (Many thanks to the awesome Basic Training Academy, Singapore for the use of the image.)

What it means is that there are a lot of athletes out there who use bodyweight in a specific way to develop movement strength, and skill, while deliberately maintaining their body mass at lean n’ mean levels to keep them lithe and sleek—after all, if performance is what you’re lookin’ for, the lighter you are, the easier bodyweight techniques will be, right? For these guys, extra pounds of muscle is nothing but drag, inertia. They don’t want it.

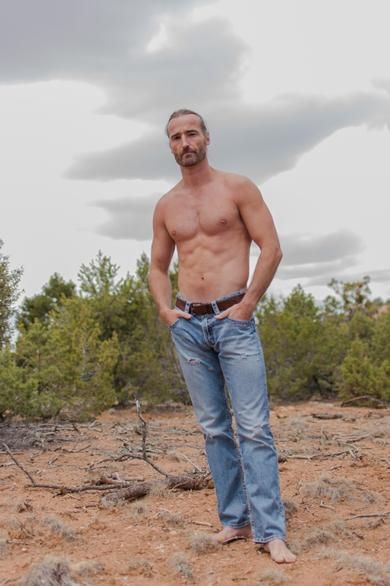

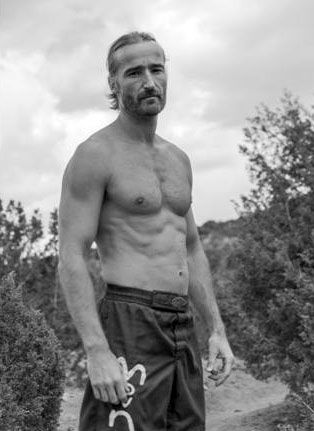

However…not everyone wants to be a clean-burnin’, high-voltage, low-weight, gazelle. Some of us want to be bulls. Big, beefy, scary-looking muthas with bulging arms, plate-armor pecs, thick, wide lats and dangerous delts. The good news is that bodyweight training can give this to you—and it can give it to you while keeping you mobile and supple, and protecting your joints.

But if extra inches of muscle are what you yearn for, you can’t train the way the gazelles train—inspiring as they are. If you want to bulk up to your maximum potential, you need to follow a different set of rules, stud. You need to religiously observe your own mass-building Commandments.

What Commandments, you ask..? Read on, future champ.

COMMANDMENT I: Embrace reps!

These days, low reps, high sets and low fatigue are the “in” methodology. Why low reps with low fatigue? Coz it’s great for building skill. If you want to get really good at a movement—be it a handstand or an elbow lever—the key is to train your nervous system. That means performing an exercise perfectly plenty of times, to beat the ideal movement pattern into your “neural map”. The best way to achieve this is to do a few low reps—not hard or long enough to burn out or get too tired—then rest for a bit and try again. Wash, rinse, repeat. This is typically how very lean, low-weight bodyweight guys train to get hugely strong but without adding too much muscle. It’s a phenomenal way to drill efficient motion-pathways into your nervous system, while keeping fresh. Like I say, it’s ideal for training a skill.

But for stacks of jacked up muscle? Sorry, this method just won’t cut it. Muscle isn’t built by training the nervous system. It’s built by training the MUSCLE! And for this, you need reps, kiddo. Lovely, lovely, reps.

To be big, you must first become weak—pay your dues with some serious reps.

To cut a long story short, you build big muscles by draining the chemical energy in your muscle cells. Over time, your body responds to this threat by accumulating greater and greater stores of chemical energy in the cells. This makes them swell, and voila—bigger muscles. But to trigger this extra storage, you gotta exhaust the chemical energy in those cells. This can only be done by hard, sustained work. Gentle work won’t do it—if the exercise is too low in intensity, the energy will come from fatty acids and other stores, rather than the precious muscle cells. Intermittent work—low reps, rest, repeat—won’t do it either, because the chemical energy in the cells rapidly regenerates when you rest, meaning stores never get dangerously low enough for the body to say “uh-oh—better stockpile bigger banks of this energy!”

The best way to exhaust the energy in your muscles is through tough, grit-yer-teeth, continuous reps. Learn to love ‘em. For huge gains, temporarily drop the single, double, and triple reps. Definitely start looking at reps over five. Six to eight is great. Double figures are even better. Twelve to fifteen is another muscle-building range. I’ve met very strong guys training with low reps for years who couldn’t build a quarter inch on their arms. They switched to performing horizontal pulls for sets of twenty reps, and gained two inches per arm in a single month! These kind of gains aren’t uncommon on Convict Conditioning, due to the insistence that you pay your dues with higher reps. They work!

COMMANDMENT II: Work Hard!

This Commandment directly follows from the last one. Using low reps, keeping fresh, and taking lots of rest between sets is a fairly easy way to train. But pushing through continuous rep after rep on hard exercises is much, much tougher. The higher the reps, the harder it gets.

Your muscles will burn and scream at you to quit. (That “burning” is your chemical energy stores being incinerated for fuel, which is exactly what you want!) Your heart-rate will shoot through the roof; you will tremble, sweat, and feel systemic stress. You may even feel nauseous.

Good! You are doing something right!

Whatever modern coaches may say, don’t be afraid of pushing yourself.

Like I say, the current trend is towards easy sets, keeping fresh, working on skill. These days you don’t “work out”, you practice. “Working ” and “pushing yourself”….these are filthy terms in gyms today. They are considered old-fashioned, from outta the seventies and eighties. (Remember those decades? When drug-free dudes in the gym actually had some f***ing muscle?) I mean Christ, some coaches take this philosophy so far that you’d think if an athlete went to “failure”, their goddam balls would drop off. Jesus!

Sure, I don’t recommend going to complete failure on bodyweight exercise—at least, most of the time. I’d prefer it if you left a little energy in your body after a set to control your movements, and maybe defend yourself if you have to. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t work hard. Damn hard.

Far from destroying you physically, brutal effort—when moderated by plenty of rest and sleep—causes the body to release testosterone, growth hormone, endorphins, and plenty of other goodies Mother Nature always intended to reward Her hunters and warriors with.

So accept the challenge. Balls, wall—together, okay? Don’t ever be afraid to push yourself into new zones of pain and effort if you want to get bigger. I have seen twigs turned into oaks this way, and you can do it too—I believe in you!

COMMANDMENT III: Use Simple, Compound Exercises!

Again, this Commandment is related to the two which have gone before. If you are going to push yourself hard on moderate-to-high reps, the exercises you are doing can’t be complex, high-skill exercises. If handstands and elbow levers cause you to concentrate to balance, you can’t overload using them—your form would collapse (and so would you) before you were pushing yourself hard enough to drain your muscles.

So if you want to work with high-skill exercises, use the low reps/keep fresh/high sets philosophy. But if you want to get swole, you need relatively low skill exercises—this is what I mean by “simple” exercises. “Simple” doesn’t mean “easy”. Doing twenty perfect one-arm pushups is “simple”—it ain’t easy!

“Simple” means relatively low-skill—it’s not the same as “easy”!

“Simple” means relatively low-skill—it’s not the same as “easy”!

Stick to exercises you can pour a huge amount of muscular effort into, without wasting nervous energy on factors like balance, coordination, gravity, body placement, etc. Dynamic exercises—where you go up and down—are generally far better than static holds, because they typically require less concentration and they drain the muscle cells more rapidly.

The best dynamic exercises are compound exercises, which involve multiple muscle groups at once. Not only are these simpler—the body works as a whole, which is more natural—but you are getting a bigger bang for your buck by working different muscles at the same time. (No weak links for you, Daniel-san.) For example, focus on:

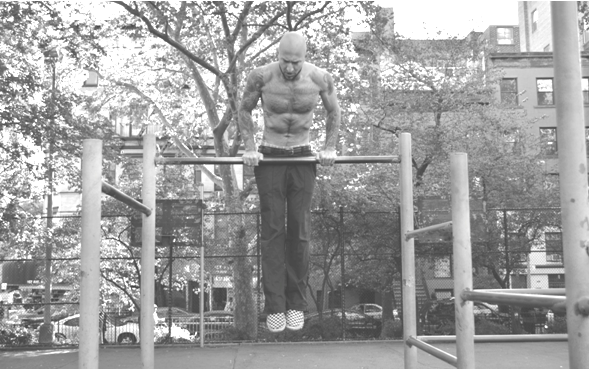

- Pullups

- Bodyweight squats, pistols and shrimp squats

- Pushups

- Australian pullup variations

- Dips

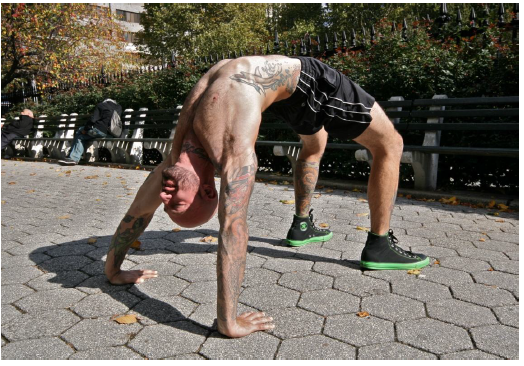

- Bridges

- Handstand pushups (against a wall—lower skill, more effort)

- Leg raises

All of these movements can be made increasingly difficult to suit your muscle-building rep range (see Commandment V). There are no excuses for not kicking your own ass, here.

Don’t get me wrong. This is not to say that skill-based techniques—like elbow levers and handstands—don’t have a place in your program. They are valuable exercises and are taught extensively as part of the PCC curriculum. But using them exclusively for muscle gain is definitely a big mistake. Throw in simple, compound moves and watch those muscles sprout like never before!

COMMANDMENT IV: Limit Sets!

This is another pretty controversial suggestion—but, as always, it flows from the previous Commandments perfectly. Why? Well, if you are hitting your body with hard exercises, and pouring that effort into enough reps to completely exhaust the muscles, why would you need to perform lots of sets?

Depleting your muscle cells beyond the point your body is comfortable with is what causes the biological “survival trigger” that tells your body to add more energy (i.e., extra muscle) for next time. That’s all you need to do. Once you have pulled that trigger and told your body to make more muscle…why keep pulling the trigger, again and again? It’s a waste of time and energy—worse in fact, because it damages the muscles further and eats into your recovery time. In the words of infamous exercise ideologist, Mike Mentzer:

“You can take a stick of dynamite and tap it with a pencil all day and it’s not going to go off. But hit it once with a hammer and ‘BANG’—it will go off!”

Many folks disagree with Mentzer’s training philosophy—I don’t agree with all of it—but he certainly nailed it when he said this. The biological switch for muscle growth needs to be triggered with a hammer, not a f***ing pencil. One hard, focused, exhausting set on a compound exercise is worth more than twenty, thirty half-hearted sets.

If you keep work sets low, you are much more likely to genuinely give your all when you train. Add sets and you subconsciously pace yourself.

I usually advise folks looking for maximum growth to perform two hard sets per exercise, following a proper warm-up. Growth will happen with one set, but two sets feels like a belt-and-braces approach. I sometimes advise more sets for beginners, but this not for growth—it’s to help them get more experience with a movement. It’s practice, basically. Once you know how to perform an exercise properly, two hard sets is all you need.

Many eager trainees ask me if they should perform more sets. The trouble is, adding sets does not encourage hard, high-performance training— just the opposite. Once you are doing five, six sets, one of two things happens; either you give your all and your last sets are pathetic compared to the first couple of sets, or you pace yourself, making all the sets weaker than they would be otherwise. Neither of these situations will promote extra growth. They just hinder recovery and increase the risk of injury.

Avoid “volume creep”. Training hard is very different from training long—in fact, the two are mutually exclusive. Keep workouts short and sharp and reap the rewards, kemosabe!

For Paul “Coach” Wade’s Bodyweight Muscle Commandments 5-10, tune in next week for part 2 of this article.

***

The models for most of these photos are the incredible Al Kavadlo and Danny Kavadlo! As ever, thanks you guys. The image of the one-arm elbow lever was provided by my buddy Jay Ding over at the Basic Training Academy. Check their site—they are doing some amazing bodyweight training, Singapore style!

***

Paul “Coach” Wade is the author of five Convict Conditioning DVD/manual programs. Click here for more information about Paul Wade, and here for more information on Convict Conditioning DVD’s and books available for purchase from the publisher.