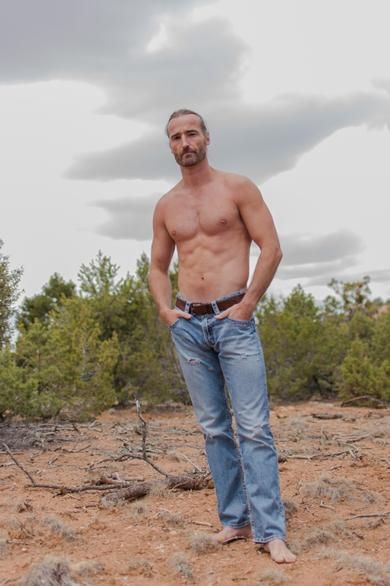

Erwan Le Corre is the founder of MovNat.

Erwan Le Corre is an icon in the fitness world. He is considered by many to be the modern-day inheritor of the French tradition of physical education (and that’s quite a compliment when you consider that the French created parkour, free running, and effectively invented the modern military “assault course”). Erwan is the founder of MovNat—an astonishing physical education and fitness system based on comprehensive movement abilities. There are many coaches who try to imitate what he does, but for people who have seen him in action—or learned from him—there will only ever be one Erwan Le Corre!

Paul “Coach” Wade (author of Convict Conditioning) recently got the chance to ask Erwan his opinion on all things bodyweight, on behalf of the PCC community. In Part I of this interview, Erwan shared his thoughts on his heroes, the thinking behind MovNat, and bodyweight efficiency.

In this second and final part of this interview, Erwan opens up about his status as “World’s Fittest Man,” his favorite bodyweight exercises, and performing sit-ups over an eight-lane superhighway!

Paul Wade: Erwan, what are your favorite bodyweight movements?

Erwan Le Corre: Probably the “muscle-up” (this name is just SO weird, what does that mean exactly?!) simply because it is such an explosive movement that demands power but also coordination and balance. It is also adaptable to different environments, not just gymnastic rings, you can do it on a tree branch, a platform, a cable or rope etc…you’re looking up and the next second you’re looking down from an elevated place. To many people it is an inapproachable feat but when you’ve trained to make it almost effortless it’s such a bliss.

But that’s thinking “bodyweight movement” for strength. You know, holding a simple deep squat, and be super relaxed in that position and hold it for a long time, this is maybe the simplest, most enjoyable human movement and position of all. How many people out there can fully squat and hold it minutes in a perfectly relaxed state? There is more to a functional, competent body than just the impressive stuff that demands strength or power.

Al Kavadlo is a master of the muscle-up!

Paul Wade: Actually, “muscle-up” still seems like a strange name to me—in jail, these were called “sentry pull-ups,” which kinda makes a little more sense!

Do you use progressions in your teaching? (For example, beginning with easier push-ups on the knees, and moving to one-arm push-ups.) If so, could you give us an example?

Erwan Le Corre: Of course! Do you seriously think I’d take a completely deconditioned person (I call them “zoo-humans”) in the woods and say, have them walk in balance across a fallen tree trunk above a raging river? That would be criminal! Where should people start? They start not in natural, unpredictable and complex environments but in controlled, or at least managed environments that are predictable and safe. Or else you don’t have a coaching and physical education system, you have no system and you’re a jackass.

So I place a 2×4 wood beam on the ground and voila, here you go, you’ve got an environment with basic, entry level of complexity but that does challenge the beginner. It demands not just “balance” but “balancing skills” and you start practicing safely and progressively that way. Another example, before you train muscle-ups you train explosive pull-ups, before you train explosive pull-ups you train regular pull-ups, before you train regular pull-ups you train a variety of hangs and hanging traverses (the “side-swing traverse”) etc…

The priority is always the establishment of movement quality and efficiency through technical work. Then you gradually increase volume, intensity and complexity. Gray Cook puts it simply like this, “First move well, then move often.” In most cases motor-skills and conditioning will develop symbiotically. Depending on the movement, and/or the environment complexity, a physical action may demand more motor-control, or more strength and conditioning. I’ve addressed this earlier but I like to hammer it because it is so important. So the way you train sometimes involves both aspects, or may dissociate them. I’ve seen guys who could do tons of pull-ups but were unable to climb on top of the horizontal bar, I mean even after trying a few times. No amount of general conditioning can compensate for a lack of motor-control and technical skill. An hour later they could climb on top 6 different ways after learning the techniques.

I also have seen guys who could do tons of pull-ups unable to climb a horizontal bar even with technical instruction, do you know why? Because the bar was too thick, smooth and slippery for them and they couldn’t hang to it very long, let alone attempting to just pull themselves up, as they simply didn’t have the necessary grip strength to do so. You’re only as strong as your weakest link, and not amount of technical instruction will compensate for a lack specific conditioning or strength. And if you want to know, all these guys were highly trained CrossFitters. Take the test I mentioned above and see how it goes. If it doesn’t go as well as you thought it would, you have two options:

– re-assess the way you train (and maybe the reason you train), and modify your training regimen consequently. Maybe take a MovNat course or certification workshop.

– just forget about it and get back to your routine.

Paul Wade: Erwan, so far I am surprised by how much your thinking has in common with what I would call the “old school calisthenics” approach to training—you make a throwaway comment “you are only as strong as your weakest link,” but very few people will realize how important that understanding really is.

What’s your personal training regime like now, in brief? How many days per week?

Erwan Le Corre: I rely on my intuition. Not everyone is endowed with good intuition about themselves, their body and what’s the best way to train, I am fortunate that I’ve got a lot of experience and I know myself well, I have explored many training modalities and mastered a few. I’m also opportunistic. If I am somewhere with water I might swim, if I’m in a gym my training will be slightly different, or in nature, or at a martial art academy, depending on what a particular place has to offer. Personally, routines are not my cup of tea, but this being said routines and programs are very important for beginners, or when you have a very specific objective, like an event you want to participate in and you want to kick ass, or at least survive. Programming IS part of MovNat. It’s just that at the moment, my training doesn’t follow a particular structure. It’s free, intuitive and opportunistic, and I am mostly maintaining a decent general level of skills and conditioning. It can change tomorrow and I can decide to structure my training again, with particular goals. There’s no rule. I also want to say that it is very important to manage health for longevity.

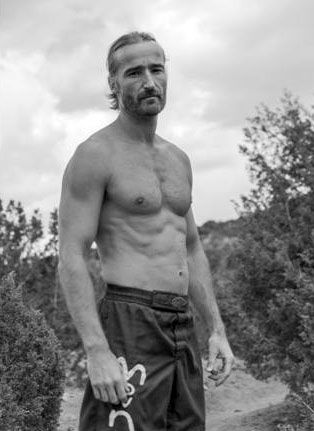

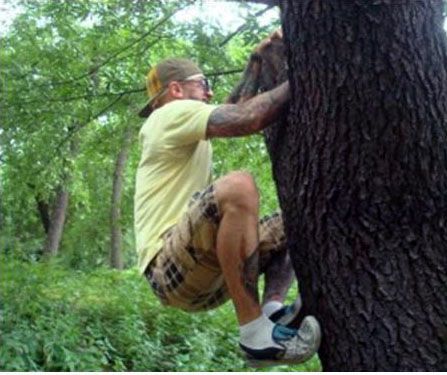

Bodyweight-based training can be opportunistic—use whatever is around you to build your skills and abilities.

There’s only so much your body can take. Aging is real. You can’t prevent it, but you can decide how fast it goes, and avoid poor lifestyle choices that make you age even faster. Overtraining and under-recovery participate in aging faster, including uncomfortable symptoms such as joint pain etc…At almost 42 I am fortunate that I experience so far very limited symptoms like that, and it has to do with the way I train, in term of movement quality but also the way I treat my body overall. If I were to tell you I train X number of days a week, or X number of hours, or X number of sets and reps, does it actually mean something THAT objective? What is the quality of each movement performed? At what intensity? How prepared is my body? How do I recover? How do I treat myself? You know the latter questions only seem more subjective, but IMO they are actually more objective than any indication of numbers. The body doesn’t know anything about numbers. It only knows about movement patterns and sensations. How you FEEL should be your number one indicator or adequate training and practice. Feel amazing and don’t settle for less. You’ve got one life. At the end of your journey you will have forgotten all the details and numbers of your programs. But you will never forget how they made you feel.

Paul Wade: An amazing attitude—a lot of advanced guys think the same way.

Guys like Demenÿ and Hébert believed that an athlete should have mastery of their body in any environment—underwater, on rough terrain, even high above the ground. You are known for having performed some very unusual feats in this tradition. (For example, Erwan famously had a sit-up competition with Jean Haberey, while both men were hanging from a bridge over an eight-lane superhighway!) Could you tell us some of the thinking behind this please?

Erwan Le Corre: I think lots of people lack motivation to exercise because the purpose behind it is either unclear or too superficial. It can be unclear when you’re aiming at general aspects of “fitness” but without ever really assessing their transferability to real use. Because of this vagueness, you need to focus on something that is more tangible to you, like number of sets and reps. That may be rational in some way, but your mind needs something more substantial and real to be really excited. My mind at least, and that which of people who train with us. Superficial goals like a better looking body are legit, but they are not deeply satisfying.

So I’m not saying that having specific goals that can be measured is unimportant, it actually is very important for a number of reasons, such as assessing progress, the effectiveness of a program and motivation for instance. All I am saying is that when there’s a truly practical goal in mind, let’s say I’m going be able to carry somebody on my back a whole mile, or I am going to train to hold my breath 3 minutes straight so I could dive and rescue someone if needed, or I will become fast at running so I could escape a threatening situation swiftly…you see, these are practical goals. The indications of the one mile firefighter carry or the 3 minutes breath hold only matter because the objectives are practical performance, but if you remove that and just look at “one mile” or “3 minutes” then it doesn’t mean much anymore.

The practical goals go beyond the current perception of what is “functional.” You step on a bosu and do rotational lunges and that’s functional. Fair enough. But what actual practical physical action are you performing? If it is not clear in your mind what you’re trying to replicate, then you might get bored very soon because it won’t click in the back of your head. Practical goals give you, and your training, a deeper sense of purpose, that increases and maintains your drive to exercise hard and consistently. Because you want to acquire real-world physical competency, or to maintain it. You want to know what you are capable of, what you are made of. There’s a sense of reality and realism that is undeniable. You can walk the streets with the self-confidence of a person who knows they won’t be completely helpless to themselves and others if a difficult situation arises. Be useful, know you are. This is a great feeling!

Paul Wade: What, in your opinion, is the biggest barrier to fitness in the modern age?

Erwan Le Corre: Mentalities. There are gyms everywhere, parks everywhere, nature, cities. There are millions of fitness videos online for people who seek motivation, and books or trainers for those who seek knowledge or guidance. But the sad reality is that the average Joe and Jane are real “zoo-humans.” Why on Earth would they even want to move or exercise? Why such a physical punishment when you can be comfy at home and hide your physical suffering with pills and entertainment? Comfort is weakening, but people seem happy to be soft, they joke about it, every TV commercial makes people laugh about useless, helpless human beings who are completely disempowered. There’s a global culture of voluntary disempowerment. It is both a mass-condition and a mass-conditioning.

Bodyweight fitness is about more than strength and huge muscles. How is your running? Your climbing, your swimming?

Change this mentality and you will have legions of people who realize that exercising, especially moving in natural ways, is not a chore, not a punishment, not an option, but an expression of their most beautiful human nature. It belongs to all of us regardless of what makes us different. It has the potential to bring us all together. I want to awake in a world crowded with self-actualized, self-empowered individuals. Instead I wake up in a world crowded with dormant minds and lazy, soft bodies. The people who train physically and want to stay healthy and strong within a society that is sick and weak are modern heroes. They may not want to be part of an elite, but in some way they are. But my point is the opposite of trying to create elites. It is rather that everyone would be liberated and empowered. I have created MovNat with this vision in mind. It is quite the romantic, utopian and delusional vision, yet I am innocent enough to believe a change will take place. In my inner world, the change is taking place NOW.

Paul Wade: Wise words, my man. Are there any long-standing myths about strength and fitness training you would like to see vanish from the face of the earth?

Erwan Le Corre: Probably the idea that all there is to fitness and building a body is to grow bigger muscles. It is not really a myth but an overwhelmingly common perception. There is more to building a body than building muscles, and there is more to building a human being than building its body. To me fitness is the level of your energy at every level, physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. This is old school, in the sense that the ancient Greeks thought like that, all the main pioneers of physical education in Europe all thought like that. They didn’t seclude themselves to a purely physical realm. They wanted people to be whole. The mainstream, commercial fitness industry has absolutely no interest in you thinking like that. You don’t make much money on self-actualized people, that’s why.

Paul Wade: You have been called The World’s Fittest Man due to your wide-range of abilities. Any final tips from the World’s Fittest Man?

Erwan Le Corre: This is one of the myths you were mentioning earlier and that needs to be debunked. Christopher McDougall, NYT Best-seller author for “Born To Run” has written in a article he wrote for Men’s Health a few years ago that I may rank as one of the fittest men on the planet. Well, it all depends on what criteria. Few people, I admit, are able to follow me in my “world” and keep up with every type of physical challenge they could encounter, on any terrain. I’ve met many inspiring specialized athletes that all could kick my ass in their specific field of predilection. I’ve met guys who are generalists, like high level CrossFitters, but who forget that reality is specific and that specific training is required for every aspect of competency you want to be ready for. But don’t be mistaken. I couldn’t care less about competition and rankings. I’m not here to prove anything, but to embody my philosophy and spread the MovNat system. All I hope is that MovNat will produce many “fittest guy on Earth.” Most importantly, just train smart and hard and become YOUR fittest, this is what truly matters. The rest is just ego. Don’t neglect areas of your physical competence and potential and leave them under-developed. It’s really a loss for yourself. Become the fittest you can be in all areas of natural human movement is probably the best tip I can share.

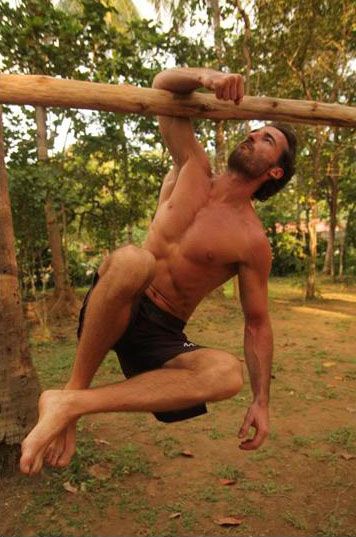

MovNat students learn to use their bodies in different environments—not just in an air-conditioned gym!

Paul Wade: Erwan, you are a phenomenal example of natural fitness! Thanks for your time.

Erwan Le Corre: Compliment taken. You’re not bad yourself! Resiliency is a beautiful thing. I want to tell people this: whatever you thought or told yourself you were, whatever you are or were told you are, it doesn’t matter anymore the moment you decide to redefine and remodel yourself into the most self-actualized person you can. ON YOUR OWN TERMS. Because if you can’t empower yourself…who will?

***

Erwan Le Corre is the founder of MovNat. To find out more about his training approach, head on over to http://www.movnat.com/.

***

Paul “Coach” Wade is the author of five Convict Conditioning DVD/manual programs. Click here for more information about Paul Wade, and here for more information on Convict Conditioning DVD’s and books available for purchase from the publisher.