One of the questions people looking to get into gymnastics or bodyweight strength training ask me is, “How much mobility or flexibility do I need in [insert body part here].”

To which I invariably reply, “It depends.”

The reason it depends is because each individual has his or her own goals that they are working towards.

First, let me define how I differentiate between mobility and flexibility:

Mobility generally refers to active movement within your given range of motion.

Flexibility generally refers to the passive movement of the joints towards the end range of motion with the goal to increase the total range.

The demands of a recreational gymnast are different from the professional athlete which are different from the serious strength trainee. And even these depend on one’s goals and level of commitment.

For example, in most athletics where you need speed, such as sprinting, football, basketball, or other sports, increasing hamstring mobility and flexibility beyond a certain point starts to decrease performance. In particular, the hamstrings need to be tight enough that the stretch-shorten cycle can activate, which helps to conserve muscular energy and provide the rubber band rebound effect that increases overall speed. If you give a sprinter the mobility and flexibility to easily move into splits like a gymnast, it will manifest as a decrease in performance.

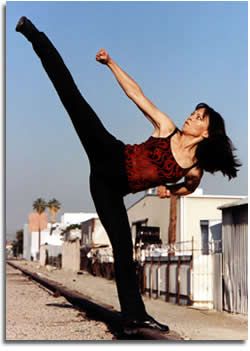

On the other hand, if you are a martial arts practitioner you definitely need a large amount of flexibility, perhaps even full splits if vertical kicks are an important part of the specific martial arts. The mobility and flexibility demands of the particular sport and the techniques they employ matter a lot for how much mobility and flexibility training you need.

Photo from: threetwoonego.files.wordpress.com

For your average recreational athlete looking to “get healthy” and perhaps develop some cool bodyweight strength movements, they may not need anymore hamstring flexibility than what is required to do a good bodyweight squat or pistol.

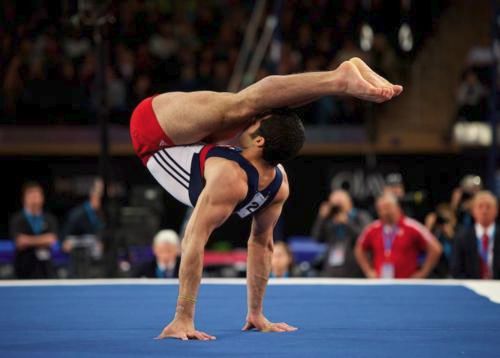

Alternatively, a specific gymnastics/bodyweight technique like the straight arm press to handstand may require significant hamstring flexibility to where you can do a full straddle or pike stretch where your chest can go to the floor.

photo from: drillsandskills.com

photo from: http://woman.thenest.com/

These different scenarios illustrate some of the conflicting nature of how much mobility and flexibility are needed to work towards certain goals.

If you are a sprinter or need great top-end speed for athletics but also want to work towards the splits or the straddle stretch for the straight arm press handstand, you need to be aware that these goals are at odds with each other. There will be trade-offs in your ability to sprint fast if you develop your flexibility beyond a certain point. If this is fine with you, then by all means do it. But the trade-offs are there whether you’re aware of them or not.

The shoulder in particular has the greatest range of motion of any joint in the body. A move like a German hang or skin the cat is good for increasing shoulder flexibility and getting the muscles and joints comfortable in an awkward position. It is also great for stretching and preparing for the back lever, which is one of the primary bodyweight isometric positions.

Photo from gymnasticswod.com

If your goal isn’t to work towards manna, then it’s unlikely that you’ll ever need this type of mobility and flexibility in the shoulders.

Photo from tumblr.com

However, the benefit of being able to move freely through a larger range of motion cannot be lost on the upper body. Unlike the lower body, where the muscles need to be tight enough to sprint effectively because of the stretch-shorten cycle, it’s very unlikely to do similar plyometric type movements with the upper body. So increasing the flexibility of the shoulders tends not to be a trade-off between various goals.

The main reason I train movements through a full range of motion over isometric or static positions is that it is better at developing strength. One of the key points within that is to become comfortable with your overall total mobility.

For example, if I was a random recreational athlete who wanted to be able to develop the back lever and many of the other gymnastics isometric positions, then becoming comfortable in a skin the cat / German hang is going to be useful. It helps you figure out how to apply force in and out of that position as well as become aware of what muscles are working when and where.

The same would be true of a squat. How can you become totally proficient with squatting if you never spend time at the bottom of the squat but only in moving through it?

This type of movement is delving into the realms between mobility and flexibility training. Maybe I don’t want to increase my shoulder hyper-extension anymore than I already have. Therefore, with the German hang, I use it as a general mobility exercise in the warm up. I can go from inverted hang down into the German hang and then pull back out. This allows me to develop the coordination, body awareness, and specific muscle activation that I need much like with moving into and out of the bottom position of the squat.

Once you have the flexibility you need, you just need to maintain it. You don’t have to spend additional time at the bottom of the position in order to stretch it out further.

So to answer the question “how much mobility or flexibility do you need?” you will have to specifically look at all of your goals and determine it from there.

If your ultimate goal is a manna then you will want to start developing the shoulder flexibility for it right away. You need the passive flexibility before you can start to apply active strength into the position. This is the two step process that should guide you through what you want to work towards.

If your goal is to be able to vertical kick for martial arts then first you have to be able to have the flexibility to do the splits. Thus, you develop your splits so as to improve your ability to actively use your legs to kick higher.

A sprinter may have all of the flexibility he needs to squat well already, while a desk job worker may need more flexibility in the calves, hamstrings, and hips in order to get down into the hole.

You need to specifically look at your body and your end goal and have a plan to bridge that gap.

Look at your goals and your current abilities

See the trade-offs, if any, and make adjustments

Train the flexibility, if needed

Then maintain with mobility work and apply active strength work

If you don’t really need more flexibility in certain joints, then you have no reason to train for it.

***

About Steven Low: Steven Low, author of Overcoming Gravity: A Systematic Approach to Gymnastics and Bodyweight Strength, is a former competitive gymnast who, in recent years, has been heavily involved in the gymnastics performance troupe, Gymkana. With his degree from the University of Maryland College Park in Biochemistry, Steven has spent thousands of hours independently researching the scientific foundations of health, fitness and nutrition. Currently Steven is pursuing a doctorate of Physical Therapy from the University of Maryland Baltimore which provides him with insights into practical care for common injuries. His training is varied and intense with a focus on gymnastics, parkour, rock climbing, and sprinting. He currently resides in his home state of Maryland. His website is http://eatmoveimprove.com.