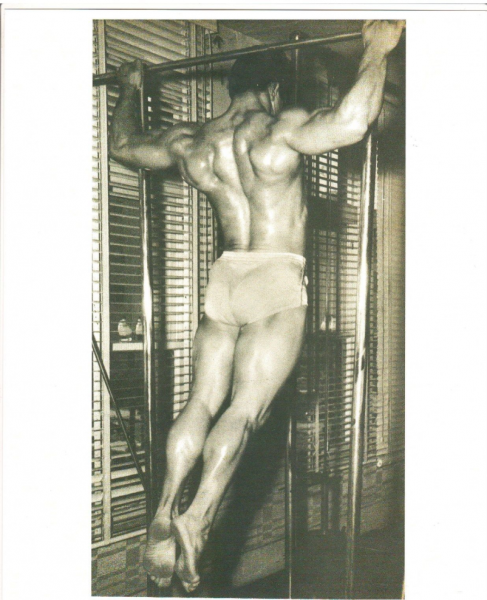

Last weekend my brother Danny and I led Dragon Door’s fifth-ever Progressive Calisthenics Certification along with PCC Team Leader Adrienne Harvey. With the rapid growth of the PCC, it’s amazing to think that it’s been less than a year since our first certification course last June in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Last weekend my brother Danny and I led Dragon Door’s fifth-ever Progressive Calisthenics Certification along with PCC Team Leader Adrienne Harvey. With the rapid growth of the PCC, it’s amazing to think that it’s been less than a year since our first certification course last June in St. Paul, Minnesota.

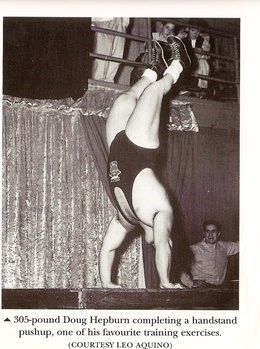

In that time, we have certified nearly 200 trainers in 3 different continents. Every one of those new PCCs is now sharing their knowledge with others and spreading the word about calisthenics. It blows my mind sometimes to think about the impact that PCC has already had on the fitness world, but we are still just getting started!

In the months ahead we have workshops booked all over the world including Ireland, Germany, Holland and Egypt. It’s amazing to travel the globe teaching calisthenics, but I’m also very excited about my hometown gig in NYC this summer.

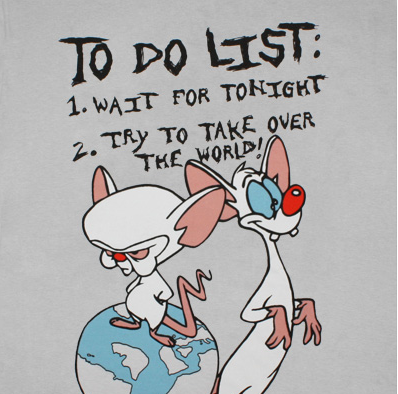

It’s beginning to feel like PCC is taking over the world!

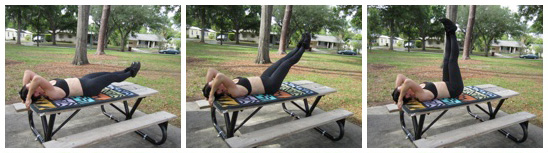

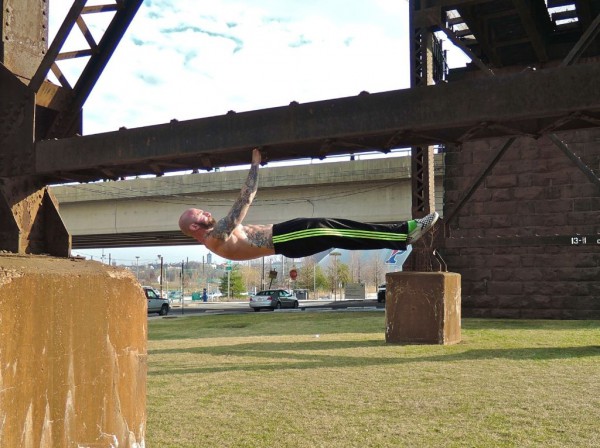

For our most recent certification, we returned to the Twin Cities. This time the event was held in Minneapolis at the city’s downtown convention center. Once again, an extremely impressive group of fitness enthusiasts, fanatics and aficionados showed up to hone their skills, inspire one another and attempt to take on The Century test to earn the title of PCC instructor. I’m proud to say that this group had our highest passing percentage yet since beginning the certification!

The caliber of candidates we’re seeing at each PCC seems to be continually improving. It’s an amazing feeling to be in a room with so many incredible bodyweight athletes who all have the same love for calisthenics. Everyone at PCC comes away with a unique experience, having both shared their own knowledge and received new ideas in return. We can all learn from one another and I am continually learning more myself each and every time we do the PCC.

If you’d like to attend (or host) a PCC event in your city, let us know in the comments section below. In the years ahead, we want to bring the PCC to as many places as possible! There’s nothing quite like the in-person experience of spending 3 intense calisthenics-filled days with other like-minded individuals.

We’re Working Out!

Al