the Dragon Door bodyweight revolution!

If you have been keeping track of the fitness world over the last five years, you have definitely heard the term bodyweight revolution used by writers and teachers.

Lots of folks have used this term, but few—if any—have defined it.

To me, if there is a common theme behind the modern bodyweight strength revolution, it’s this:

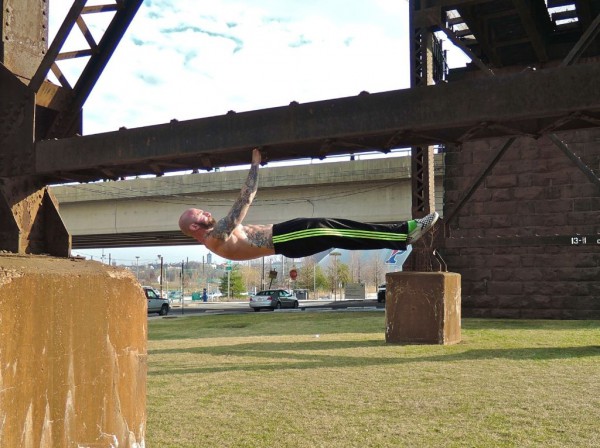

Cutting edge athletes and coaches are starting to break down the distinction between bodyweight training and externally-weighted methods for adding strength and muscle mass.

What does that mean?

Well, up till fairly recently, the fitness “status quo” treated bodyweight training and, say, weight-training very differently. Weight-training was done to get ya big and strong as possible. To achieve this, you were supposed to follow three basic rules:

- Train hard for strength and mass. (A given. No pain, no gain, bitches!)

- Be progressive. (The goal is always: add weight to the bar!)

- Focus on load, not reps. (Folks will ask: how much can you bench? Not; how many reps?)

Fairly simple, huh?

And it worked, too. For the last fifty or so years, barbells and dumbbells have been the “go-to” method for bodybuilders and strength trainers alike. Some coaches and exercise ideologists have gotten so wrapped up in the romance of the iron, that they have told us that these tools are the only way to maximize muscle and power. (This is horseshit, but you know that already, right?)

Compare this model with bodyweight training. Over the last forty-plus years, personal trainers, writers and fitness coaches have been force-feeding the world with a philosophy of bodyweight training which is built on the following three principles:

- Train moderately for skill or conditioning. (e.g., soccer drills, circuit training)

- You can’t be progressive with load. (Sure, you can add weight to pullups, but then you are weight-training, right?)

- Build to high reps. (How many pushups can you do?)

Notice something? The bodyweight training principles are pretty much the diametric opposite of the weight-training principles! Why? Because it was figured that there was no point in treating calisthenics like a PROPER strength and muscle discipline, coz there was no way to make the load progressive. For this reason, bodyweight training ceased to be viewed as a power and strength method. It became relegated to a “fitness” method, or for a warm-up, prior to the weights. Worse still, it was viewed as a means for “light toning”. (Puke now, ye who have the buckets readied.)

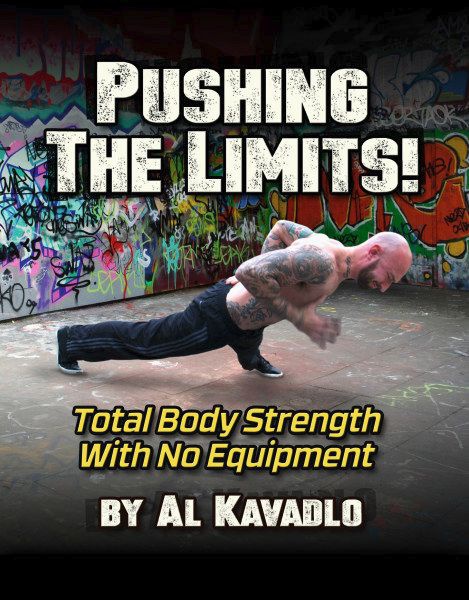

Recent conditioning icons have shattered this illusion, and are actually bringing intelligent athletes round to the notion that you can break any bodyweight exercise into progressive chunks—all the way from easy rehab work, up to the hardest strength exercises know to mankind. I’m talking about revolutionary books like Al Kavadlo’s Pushing the Limits! and Raising the Bar; Brooks Kubik’s wonderful Dinosaur Bodyweight Training; and Pavel’s breakthrough Naked Warrior.

Give me a break!

This is the idea at the very heart of the modern bodyweight revolution. If you can use external weights progressively—in hard sessions designed to build load over time—why can’t you do the same using your body’s own weight? The answer is, of course, you can. You don’t need to treat bodyweight as a gymnastics or sports skill, or as a warm-up, or as a simple endurance discipline. You can do it progressively, just like weight-training. All you need is a solid understanding of the science of bodyweight progressions. And this is why the Progressive Calisthenics Certification (PCC) organization was born, to catalog and disseminate this traditional knowledge to anyone in the fitness world who wants it.

A lot of athletes—specially those already in the bodybuilding or powerlifting world—have taken this breakdown in the barriers between regular lifting and bodyweight training approach real literally. Hell, why not apply regular lifting templates to bodyweight training? This is what many have tried to do; and in this article I’ll discuss some ways of doing it. I’ll also show you a good alternative used by my own teacher, Joe Hartigen.

The CC-Style Template

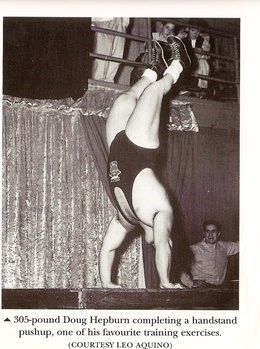

When it comes to sets and reps, I generally prefer a real simple, old school, American-style double progression. You warm up with some fairly easy exercises, then hit your major technique hard for two-to-three sets. When you hit your rep goal, you move to a tougher exercise. Don’t go to failure—always leave a little energy left in your limbs to complete an exercise safely, or in case you need to defend yourself. That’s the Convict Conditioning approach—and trust me, it works just as well for weight-training as it does for calisthenics. Many old school bodybuilders and strength athletes have used this kind of program with great success—it’s not a million miles away from the sort of training performed by old school strength marvels like Doug Hepburn, or modern-day bodybuilding champions like Dorian Yates.

Hepburn—like all the ultra-strong old-timers—used bodyweight training alongside his lifting. He also trained infrequently, going all-out with low sets. Sound familiar?

Popular Strength/Mass Templates

Of course, there are other rep/set formats than the CC approach. Dozens. Here’s a roll-call of a few well-known ones:

- The 5×5 system

- Pyramid training

- Ladders

- Heavy singles

All of these popular weight-training approaches can be used with bodyweight—in fact, they are being used right now. But no method is perfect, and there are problems when applying these methods.

Using singles is a good example. A heavy singles workout might consist of, say 10 sets of 1 rep, using 85% of your max. This is pretty easy to accomplish if you are working with your bench press; but it’s a lot tougher to translate it to your bodyweight pushups. For a start, how do you define “85%” of effort accurately? Which pushup progression do you select? With the bench press, you can add a tiny increment, maybe 2lbs to the bar every so often. How do you add such microscopic increments to your pushup form? How do you maintain this system, long-term with such fuzzy variables? You are kinda pissing in the wind here.

A bigger problem with most training systems is that they waste the athlete’s precious energy. A really great rule of thumb in muscle and strength work is that the degree to which your body adapts is proportionate to the stress you put it through. But what athletes constantly forget is that the muscle-building and strength stimulus is based on your best set, it’s not spread over your other sets! As I’ve said elsewhere:

To put that shit simply, if you want to get diesel, you need to do a lot of work in a single, relatively brief set. Your peak set! Trouble is, a lot of athletes are in the habit of exhausting themselves before they reach that peak set.

To put that shit simply, if you want to get diesel, you need to do a lot of work in a single, relatively brief set. Your peak set! Trouble is, a lot of athletes are in the habit of exhausting themselves before they reach that peak set.

Bodybuilding is possibly to blame for this. Back in the seventies and eighties, it was all about “pyramiding”; you would typically warm up with 15, 12, 10 and 8 reps before knocking out a few peak sets of 6-8—then you would reverse the process. (You go up in weight, then down, hence the term “pyramid”.) The problem with this was that by the time you had done the first four sets you were too shot to do very much in your peak sets! Then you would repeat all those lighter, higher-rep sets again, just adding more volume to eat into an already overloaded recovery system.

The same problem is true of the popular “ladders” method of training. With ladders, you start with one rep—say, a pullup—then take a short break, and do two pullups. Break, then three. All the way up to your peak set, of, say, five reps. Then you take a short breather, do four reps, then break, then three, and so on down to one rep. See the problem with this? If your peak/best set here is the five rep set, you will have already done TEN reps of that exercise before you reach it! If the five reps really represent your best, then doing ten reps of the same beforehand is definitely going to adversely affect your performance in the five. In essence, ladders are a good way of doing a lot of work, but a pretty imperfect way of doing high quality sets.

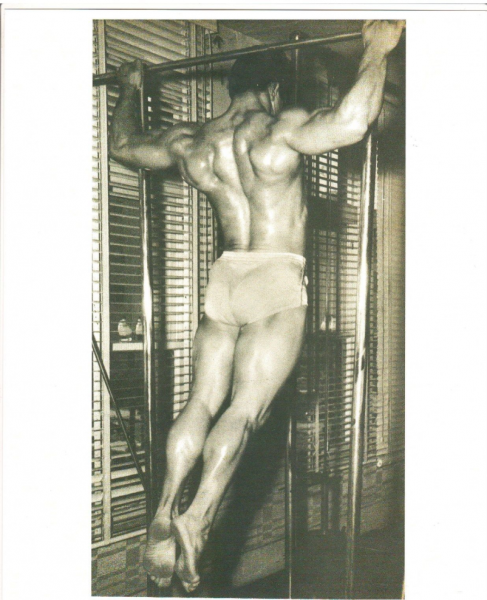

5×5 is a more traditional method—it was used by Arnold’s hero, Reg Park, back in the fifties.

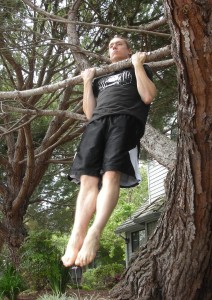

rocking some behind-the-neck pullups.

Park’s method was to use two warm-up sets of five, then three sets of five with the heaviest weight you can handle for a particular exercise. Once you can hit the 3×5, you go up in weight.

It’s a simple (and pretty effective) idea. The problem—in terms of hitting one great, “peak” set—is that it makes you hold yourself back. You are inevitably (even if only subconsciously) holding yourself back from giving your all on the first hard set, in order to get the five reps on the final two sets. You need to do this, because if you really gave your all grinding out five reps on the first heavy set, you would be pretty unlikely to be able to repeat that twice. So with 5×5 you never have the motivation to really give your all and hit that one peak set.

Enter the Mentor: Joe Hartigen

One template which doesn’t contain any of these problems was taught to me in the 1980’s by my mentor, Joe Hartigen. Joe was a bona-fide calisthenics master, and although he was in his seventies when I met him, he was much more powerful than me, and remained incredibly strong in pulling movements right up to the final year of his life. Joe had forgotten more about training methods and the history of physical culture than I will ever know, and I learned virtually all the progressions in Convict Conditioning from him.

Despite the fact that Joe was an icon to me—and several others in San Quentin—we didn’t train in exactly the same way. We had different backgrounds, for one thing. I came from a “new school” calisthenics approach, one based on building up high reps in squats, sit-ups, pullups and (especially) pushups. In fact I would often return to these high-rep workouts—often ultra-endurance bodyweight work—throughout my time inside, particularly in Angola. (Think “thousand pushup days” and you got the idea.)

Joe was very much a man who favored lower, more intense, higher quality reps. He typically shook his head when he looked at my training journals, and—likewise—I must admit that when I was younger and dumber, I possibly looked down on his methods as a bit old-fashioned. Like a cool photograph, but colored in sepia. In later years, I realized he was right on the money, and although I modified my own training to better match his thinking, our workout styles were never quite the same.

The Hartigen Method

When it came to sets and reps, Joe had a pretty fixed method for working out. I’ve never heard a name for this scheme, so I’m gonna call it The Hartigen Method (although there’s no way he was the first to use it). This approach is simple to apply, allows for the use of real hard exercises, and is progressive—so I thought I’d put it out there for any ex-lifters or strength athletes looking for a new way to work with bodyweight exercises.

Here’s how it works:

1. Pick the hardest exercise you can do for 5 reps in good form.

2. Warm up, and perform a 5 rep set.

3. Rest approximately 1 minute. Shake your muscles loose as you rest.

4. Perform 4 reps of the same exercise.

5. Rest approximately 1 minute. Shake your muscles loose as you rest.

6. Perform 3 reps of the same exercise.

7. Repeat this procedure until you have performed a single rep.

That’s it! In essence, Joe picked an exercise he could do five good, strict reps with, and did 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

It’s that simple. Joe’s theory was that if you could bust out five reps of an exercise you were working on, then after a minute’s rest, you should be able to do four reps. After another minute, you should be able to do three, and so on. Joe felt this rep scheme offered low reps for strength and muscle, but also enough reps—fifteen total—to give an athlete plenty of hard practice on an exercise, but without burning out.

Plus, using this method you can hit an exercise hard in under ten minutes. Even if you were working with four exercises in a workout (two or three would be better!) you could be done in half an hour. Joe’s method works great with weights, too—kettlebell presses and rows would be a wonderful superset, if you’re that way inclined. (5 presses, a minute’s rest, 5 rows, a minute’s rest, 4 presses, etc.) You could superset pushup and pullup exercises the same way.

Making progress

Progression couldn’t be simpler with this method. When you can do all 15 reps—that is, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1—for three workouts in a row, you move to a slightly harder version of the exercise. As with all bodyweight strength, having an extensive toolbox of progressions is key to moving forward; it’s also why the PCC Instructors’ Manual includes hundreds of progressive exercises.

There will be times you don’t get 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. You may only get 5, 3, 2, 1, 1. That’s fine, and to be embraced. When you don’t get the full 15, use these principles to move forward:

Try to add a rep (or two) next time; shoot for 5, 4, 2, 1, 1, then 5, 4, 3, 1, 1, and so on.

Whatever you get, always push yourself hard on the first set—that’s your peak set.

Adding reps on the earlier sets is more valuable than adding reps on the final sets.

Never do more reps than you are aiming for; stick with 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Aim to perform ALL five sets, even if those sets are very low rep; e.g., 3, 2, 1, 1, 1.

Exercises, post-set work and warm-ups

Joe often performed more exercises than I stuck to. Most people today would probably call his routine imbalanced. In particular, he loved hanging exercises, and would do all kinds of weird variations of pullups, leg raises, levers, holds and hangs. Strangely, despite being such an aficionado of hanging work, he would typically do only three exercises for the rest of his body—one-leg squats, flat one-arm pushups, and some kind of inversion; handstands, but often headstands (I rarely saw him do inverse pressing, these were typically static). I have watched Joe do bridges, and do them easily, but like the man himself, these were an exception rather than a rule.

Whatever his last exercise of the session was, Joe would often make his very final set harder by completing a ten second dynamic-tension isometric at the top position of that very last rep. He’d follow this with a slow negative of about ten seconds. He claimed that this little “trick” for finishing his workout told his body that the session was over, and increased his hormonal profile. I’m not sure that’s true, but if Joe’s physique—at over seven decades—was testament, then he knew what he was talking about.

you can squeeze it at the top for an isometric benefit.

What about a warm-up? Interestingly—like Reg Park—Joe never went over five reps on his warm-up sets. He would typically do two or three warm-up sets of five reps, and he always applied Charles Atlas-style dynamic tension during his warm-ups. If he was doing an exercise like one-arm pullups, he would perform an exercise about half as tough on his warm-ups—two-arm pullups. Always five reps. Why not more? Joe felt that you should always train to meet your goals. His peak sets were always five reps, so he thought if he did more in his warm-ups, his body would get confused and start adapting to higher reps instead! I’m not certain I agree with that, but it gives you some food for thought, eh?

I often advocate using progressive exercises when warming up—maybe start with a real easy exercise for high reps, then follow with a slightly harder exercise for less reps. But Joe only ever used one exercise technique in his warm-ups, no matter how many warm-up sets he did. I used to wonder why, for example, he’d perform two sets of regular pullups before his one-arm work; why not one set of regular two-arms, then something harder, like assisted pullups? I asked him once. Because I can make the two-arms as hard as assisted pullups, dumbass! he replied. And it was true. His capacity to tense his muscles during training—dynamic tension—was so profound, he could make seemingly easy exercises as seem as hard as advanced ones. He was able to adjust the intensity of any exercise by 100% or 1%, just using the power of his mind.

That was how profound his body wisdom was. Not many athletes could aspire to this level, although it’s possible with time and patience. I still admire the man to this day!

Lights Out!

Well, that’s it from me. Thanks again for reading—it means a lot to this dopey fella that you guys and gals still take the time to read my weathered musings. I hope this article has given you a new idea to play with. Looking for a lower-rep strength and mass routine that fits well with bodyweight? Give The Hartigen Method a try…tonight!

Oh, and if you liked hearing about Joe’s attitude to training, check this article out. I wrote it for my good buddy Neil Bednar.

You could do a lot worse than modeling your training around old Joe’s philosophy. That brother was something else!

***

Paul “Coach” Wade is the author of five Convict Conditioning DVD/manual programs. Click here for more information about Paul Wade, and here for more information on Convict Conditioning DVD’s and books available for purchase from the publisher.