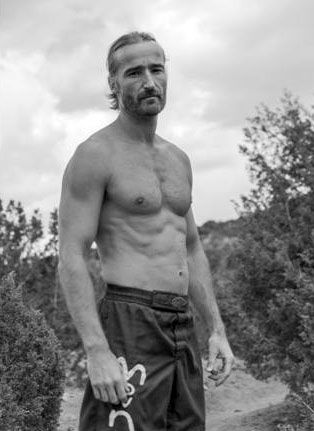

Erwan Le Corre is an icon in modern fitness. Men’s Health once declared that he ranked amongst the fittest men in the world. Whatever your personal definition of “fitness”, Erwan undeniably has an amazing pedigree; in fact he is considered by many researchers to be the modern-day inheritor of the French Physical Education tradition.

Erwan spent his childhood exploring the countryside and training in the martial arts. He went on to become the most famous protégé of Jean Haberey, the notorious French stuntman and athlete. Haberey’s students met at night, and climbed bridges, ran and jumped across the urban skyline, and fought hand-to-hand in sewers. Haberey‘s underground society—dubbed Combat Vital—is widely considered to be an important forerunner of the modern bodyweight arts parkour and free running.

After seven years, Erwan left Combat Vital, and plunged into an intense period of in-depth research into traditional training methods. The result of these years of study and experiment was MovNat, Erwan’s physical education and fitness system which promotes authentic, natural movement through activities such as running, crawling, climbing and swimming.

Paul “Coach” Wade (author of Convict Conditioning) recently got the chance to ask Erwan his opinion on all things bodyweight, on behalf of the PCC community. The two-part interview that follows presents a unique insight into Erwan’s radical—and powerful—training philosophy. Erwan goes in-depth and pulls no punches, telling us exactly what is right with modern training—and also what’s very, very wrong.

If you are interested in bodyweight strength or movement training, you do not want to miss this!

Paul Wade: Erwan, thanks for agreeing to answer a few questions. Many people see you as the modern inheritor of a long tradition of “natural” physical culture.

Who is your all-time hero in physical culture, and why?

Erwan Le Corre: Paul thanks for inviting me, it’s appreciated.

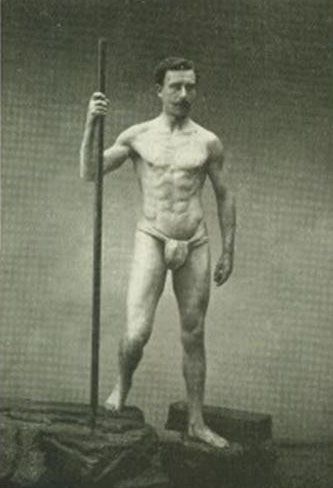

First off I would like to dissociate Physical Culture on the one hand and Physical Education on the other. Historically there is some overlap between the two, but physical culture was mainly orientated towards feats of strength and the development of sculptural physiques. The term “culturist” comes from it, and is the forerunner of modern bodybuilding. Think Eugen Sandow or P.H. Clias for instance, the “Arnolds” of their time. I’m not saying they were not physical educators in some way, but in this regard there is, in my opinion, more substance to find when looking at the history of Physical Education.

Physical educators of the past had at heart the complete physical development of young people and the general population. So their aim was not just strength or sculptural physiques as in Physical Culture, but a more harmonious, general, and practical development of the body and mind. The type of “gymnastics” and “calisthenics” they promoted had not so much to do with a modern approach to gymnastics and calisthenics, in the sense that a lot of the training was based on practical skills. Movement skills practice such as jumping, running, climbing, throwing, carrying etc…were not done just for aesthetics, and not just for general physical conditioning through bodyweight exercise. The approach was way more practical, with exercises strongly resembling real-world physical actions and apparatus mimicking the environmental and situational demands of the real-world (there was also often a strong correlation with military needs and nationalistic ideas).

So of course my personal, all-time hero is the famous French physical education pioneer Georges Hebert. The reason is that he did emphasize utilitarian training as well as contact with nature like I do. He’s my big inspiration, though not the only one. But the history of physical education doesn’t start or end with him. There were wonderful other pioneers before him (who did strongly inspire Hebert, such as Amoros or Jahn), and there are quite competent innovators that came after him too. Sorry for the discourse in Physical Education history in Europe, I hope more people start to understand that “functional fitness” didn’t start with kettlebells or modern calisthenics. There’s a LONG line of people before us and a long history of methods, systems and programs. There’s nothing new under the sun!

Paul Wade: There’s no doubt about it—you’re right, there’s nothing new in physical training. Nothing good, anyway! Let’s look a little at how you go about “Physical Education”. A lot of MovNat seems to be based around moving the body in different ways. “Body competency” seems to be a huge part of what you and MovNat are about. Could you tell us a little about your philosophy of bodyweight training?

Erwan Le Corre: Well, prepare for a lengthy answer! MovNat is based around moving the human body in all the ways that are natural to it. To understand what “natural” entails from our perspective, you want to imagine a wild human animal, maybe one of our common ancestors, or one of the remaining ancestral hunter-gatherers, moving through natural environments for survival. Having to seize opportunities while avoiding threats. Unless they’re resting, playing or dancing, the movements they will have to perform are all PRACTICAL; they aim at doing something immediately useful in a variety of situations of the real life. Secondly they are ADAPTABLE, they must adapt to the physical environment where you are.

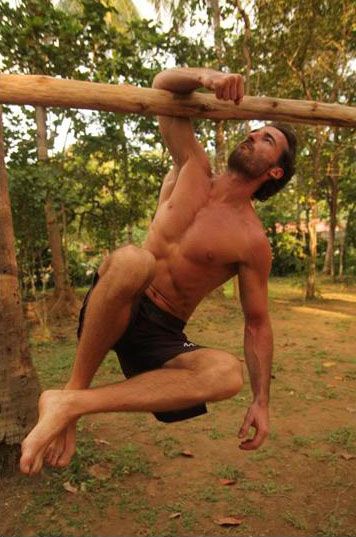

This simple observation has a lot to do with the way we approach physical training in MovNat. First off we focus on the practicality of the movements we train. For instance performing a “human flag” does have value from a bodyweight strength standpoint, but not so much from a practical standpoint; therefore it may be trained occasionally as part of your overall physical experience and background. Comparatively, significantly more attention and energy will be dedicated to actually practical climbing techniques, for instance a “tuck pop-up”, or climbing strength and conditioning movements, for instance the “forearm pull-up” which is the discrete component of the “tuck pop-up” that requires more power.

Environmental adaptability is the second main pillar of our philosophy. If you train a given jumping technique, say a broad jump, you are not just considering the strength gain and other physiological adaptations by training this movement at a greater volume or intensity. You are also looking at finely tuning your motor-control skills by increasing environmental complexity. Greater environmental complexity means a physical environment that becomes progressively more challenging. This can be starting first by jumping at ground level on a flat floor, then landing on a flat but restricted surface (still at ground level), then jumping from and/or landing on a small, slightly elevated surface, and ultimately performing a similar jumping technique but at a height, landing on a narrow, uneven surface, and potentially involving a danger in case of a fall.

That’s an example of progression in (environmental) complexity, without necessarily an increase in volume or intensity. The movement pattern remains the same, the volume and intensity too, but you must finely tune your motor-control if you want to be both effective (doing it successfully) and efficient (with minimal energy expenditure, in the shortest time, in a mentally relaxed state etc…). You see there is more to greater performance than just volume and intensity. When you add to the mix the necessity to increase movement adaptability, you open a whole new world of possibilities and challenges. It can be intimidating to those who prefer not challenging their comfort zone too much, but it is going to thrill those who want optimum preparedness for the real world. No extra amount of general conditioning will ever compensate for a lack of motor-skills and adaptability.

So yes, physical competency to us is movement competence and to develop it you need motor-skills, strength and other aspects of conditioning. This being said, we are not restricted to bodyweight. To us bodyweight just means locomotive skills such as running, jumping, crawling, balancing, climbing etc…i.e., moving your body through various environments. Sometimes, you need to move both your body and an external object, and your bodyweight movement becomes a manipulative action against greater resistance if for instance you’re lifting and carrying something heavy, and this is practical and adaptable training too.

I like to tell people, especially the big dudes who are mostly focused on strength and lifting heavy, that before they moving “heavy s**t”, they must be able to move the “heavy s**t” that they are. They usually get it because the heavier you get in bodyweight, the more difficult it can become to move your body with complex movements and through complex environments. They know it and can feel it inside, so it is hard to argue with something that just makes sense.

So physical competency starts with being to move your own body skillfully before anything else. My good friend Gray Cook says, “Don’t add strength to dysfunction” and he is so damn right. This simple common-sense is probably what led him to create the CK-FMS, so that kettlebell practitioners who primarily focus on the external load, manipulative side of exercise, would rediscover fundamental human movements and positions. After fixing basic dysfunctions they can better put their strength to use, or develop even more strength once they got rid of physical limitations, such as lacking full range of mobility. Move your body skillfully first, then skillfully move stuff around, not the other way around.

Paul Wade: I am in agreement with this, completely. It’s ridiculous how many people I see trying to squat with loaded barbells when they can’t even squat properly with their own bodyweight. A lot of the older generations of lifters and bodybuilders (pre-1960s) all did bodyweight work before, and alongside their weighted training to keep these essential skills at a high level.

Your attitude to “practical” movements is really interesting. These days, people are beginning to realize that calisthenics is about more than formal exercises like push-ups and sit-ups; bodyweight training can encompass a massive range of activities including “natural” exercises like crawling, balancing, jumping, and so on. I tend to think that both these types of bodyweight work—the formal/systematic, and the free/natural—work really well side-by-side in a training program.

What kind of role do more formal, traditional exercises (e.g., pull-ups, push-ups, bodyweight squats) have in your method?

Erwan Le Corre: People start rediscovering movement as whole, and there’s a slow shift of perception and paradigm towards a more movement-based approach to fitness. So far movements, usually basic, segmental and mechanistic movements have been used for the purpose of muscle building, strength or conditioning. With MovNat the approach is different, as the purpose of movement is movement itself, or movement competency if you prefer.

Muscles and joints are the tools, much less a finality. This being said, to perform practical movements effectively you do need a functional body that is also conditioned and strong. You will need full range of mobility, stability and strength, power, coordination, endurance, spatial awareness (proprioception and exteroception), and so on.

To answer your question more specifically, most formal strength and conditioning drills such as pull-ups have their place in our method all simply because they ARE natural movements too. Let me explain, what exactly is a pull-up? From a classic strength and conditioning standpoint it is an upper body strength conditioning drill. From a MovNat standpoint, it is a climbing movement. If you hang for instance to a horizontal tree branch and that you pull your body up, the end-goal is most likely that you intend to actually climb on top, right? You see, the movement itself hasn’t changed, but the intention and purpose have, as well as your perception of the drill. It is replacing movement in its original practical context. The strengthening value of the pull-up drill is the same, and we will practice it to develop upper body strength in the trunk, arms, shoulders, abs, forearms etc…so we can condition for more complex climbing techniques. Where our approach will differ is that we will try perform various practical ways to pull-up, for instance hanging from a much thicker surface or a flat surface, pulling hanging from your forearms (we call it “forearm pull-up”) etc…so we can adapt to specific environmental demands with effectiveness and efficiency. This is why for instance a “chin-up” (supinated grip) has much less value to us than a “pull-up” (pronated grip) chin to the bar or higher. Why? Because if you think climbing a horizontal surface and pull your body up chin to the bar, what do you do next? That’s right, you’re forced to bring each arm behind and over the bar so you can keep climbing. It is a waste of time and energy, it is inefficient.

You see, just being good at pull-ups won’t necessarily translate to effectiveness or efficiency in every climbing movement or surface. It is important and even essential, but not sufficient at all. The reason is that both motor-skill and conditioning need specific training and adaptation. Think SAID principle, i.e., Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demand. This is why we don’t believe in just training in a (usually) short selection of general conditioning drills, because the “reality of reality” is that more specific demands can be placed upon you and your body won’t respond effectively and/or efficiently unless it has been trained to perform specifically. To us, “GPP” (general physical preparedness) programs do work, but work only to an extent. Contrary to a common belief, our observation is that they do not prepare you for “anything”, and people with a GPP training background who come train with us realize this. Within seconds or minutes. Again, most people don’t just lack techniques and motor-control, and MovNat is not just that (a set of techniques), they also lack specific conditioning and MovNat also addresses specific conditioning (not specialized conditioning).

I hope it all makes sense! If people in your audience want to understand this approach from an experiential standpoint, I invite them to find a bar that is about 4 inches thick (such as these metal structures for swings in kid’s playgrounds) and perform these 2 tests:

-max reps (pronated grip) pull-ups (compare to max reps with regular pull-up bar). If the number is significantly lower than what you can normally do, you lack grip strength. Isn’t it part of strength conditioning?

-starting from a full dead-hang (no motion at all), climb on top of the bar until you can straddle on top of it. You can’t jump off the ground, you can’t pull on something else than the bar itself, you can’t push off anything with your feet (like the vertical poles on the side). How many ways can you climb on top? How many ways do you know, and how many ways can you actually perform? For each technique you’ve used, how easy and efficient was it? If you couldn’t climb on top once, maybe you lack technique and motor-control, maybe you lack specific strength and conditioning, or maybe a combination of both. Same answer if you could only succeed climbing on top using one particular movement. You should be able to use 3 different ways at least, and ideally all 6 ways we teach in MovNat.

Next week we’ll post part II of this interview, where Erwan talks about his approach to training progressions, motor skills, training longevity, and debunks longstanding training myths—plus much more. Not to be missed!

***

Erwan Le Corre is the founder of MovNat. To find out more about his training approach, head on over to http://www.movnat.com/.

***

Paul “Coach” Wade is the author of five Convict Conditioning DVD/manual programs. Click here for more information about Paul Wade, and here for more information on Convict Conditioning DVD’s and books available for purchase from the publisher.